There are a million ways to kill a cellphone. Disposing of the body isn’t so easy.

You might have several cellphones tell-tale hearting you from a darkened drawer. The phone whose battery died. The one you drowned. The one you ‘bricked’ by putting the wrong passcode in too many times.

Eventually, you need to get rid of some bigger electronic waste (e-waste). A widescreen with missing pixels. A noisy desktop computer. With your inner Marie Kondo breathing down your neck, you throw it all in the trunk with your dead cells and take a trip to the dump.

You’re not alone.

Visualizing The World’s E-Waste Problem

We were shocked to learn the latest figures from the Global E-waste Monitor 2020 report and decided to do something about it to help educate others. The images below will help you visualize the sheer amount of computers, mobile phones and other electronic products with a battery or plug we discard every day, month and year.

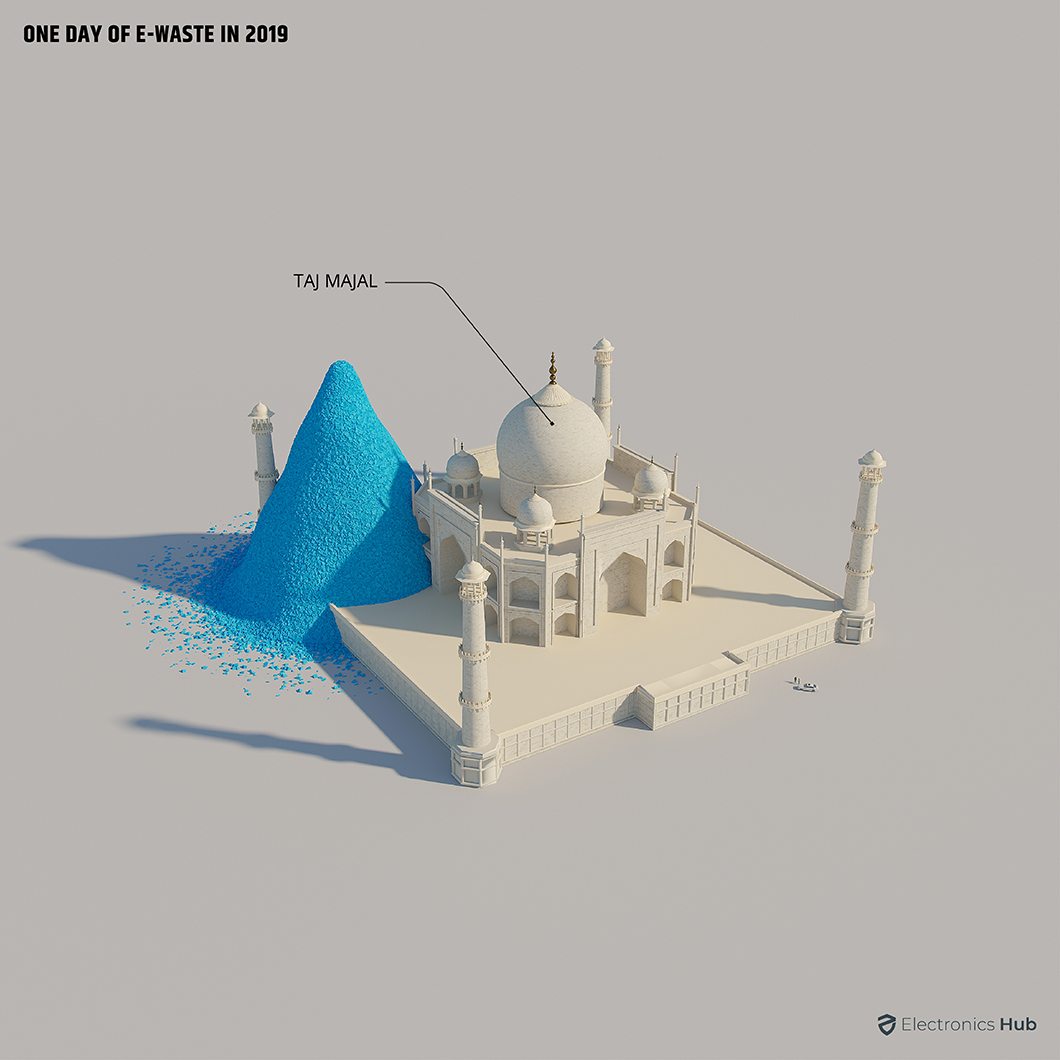

An e-waste Taj Mahal every day

Every day in 2019, humans produced 140,000 metric tons of electronic waste. Our researchers calculated that if this e-waste was made up entirely of bricked iPhone 11s, you could use those bricks to rebuild the Taj Mahal:

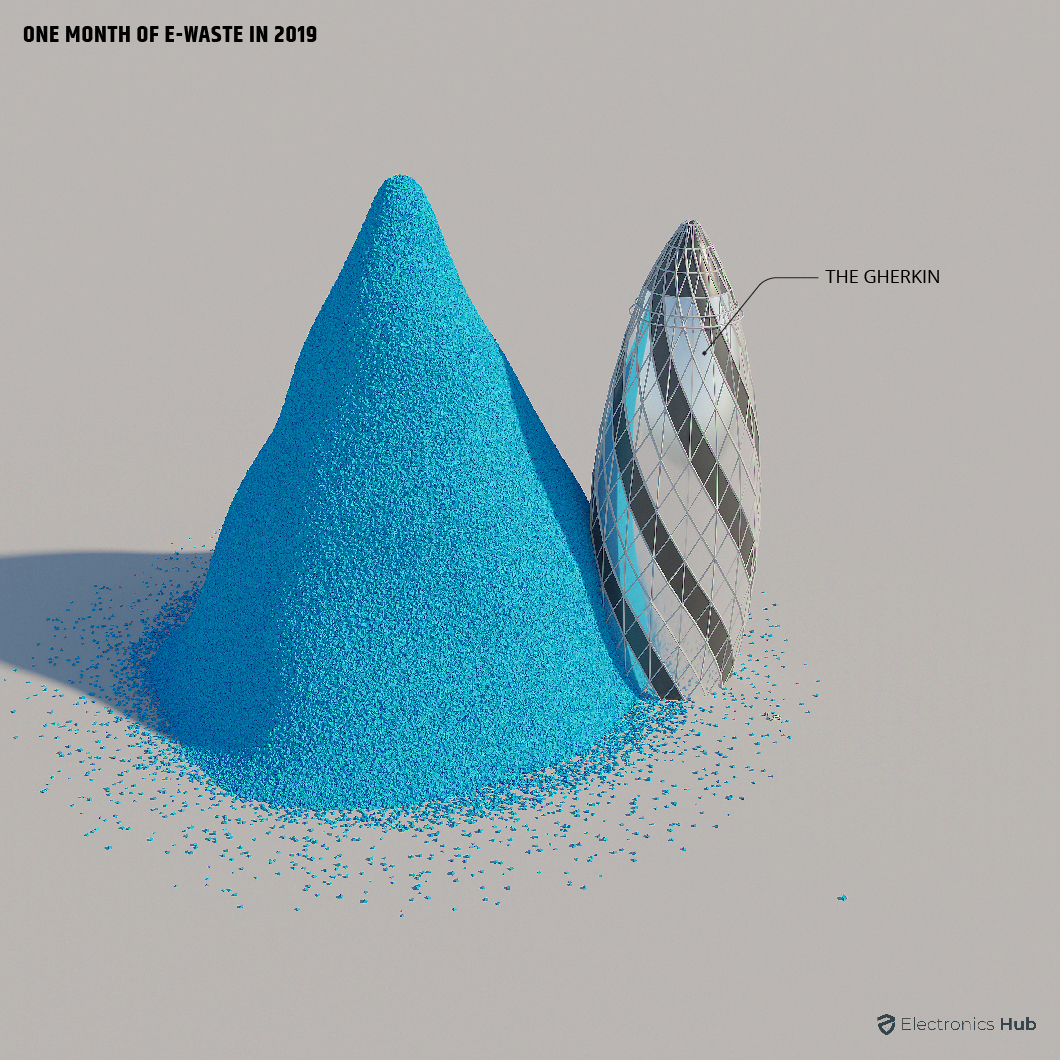

An e-waste Gherkin every month

Every month, the world produces a pile of e-waste bricks that would dwarf London’s 180-meter Gherkin skyscraper – 4.47 million metric tons to be more precise.

As of 2019, just 17.4% of the world’s e-waste was ‘officially documented as properly collected and recycled,’ according to the Global E-waste Monitor 2020.

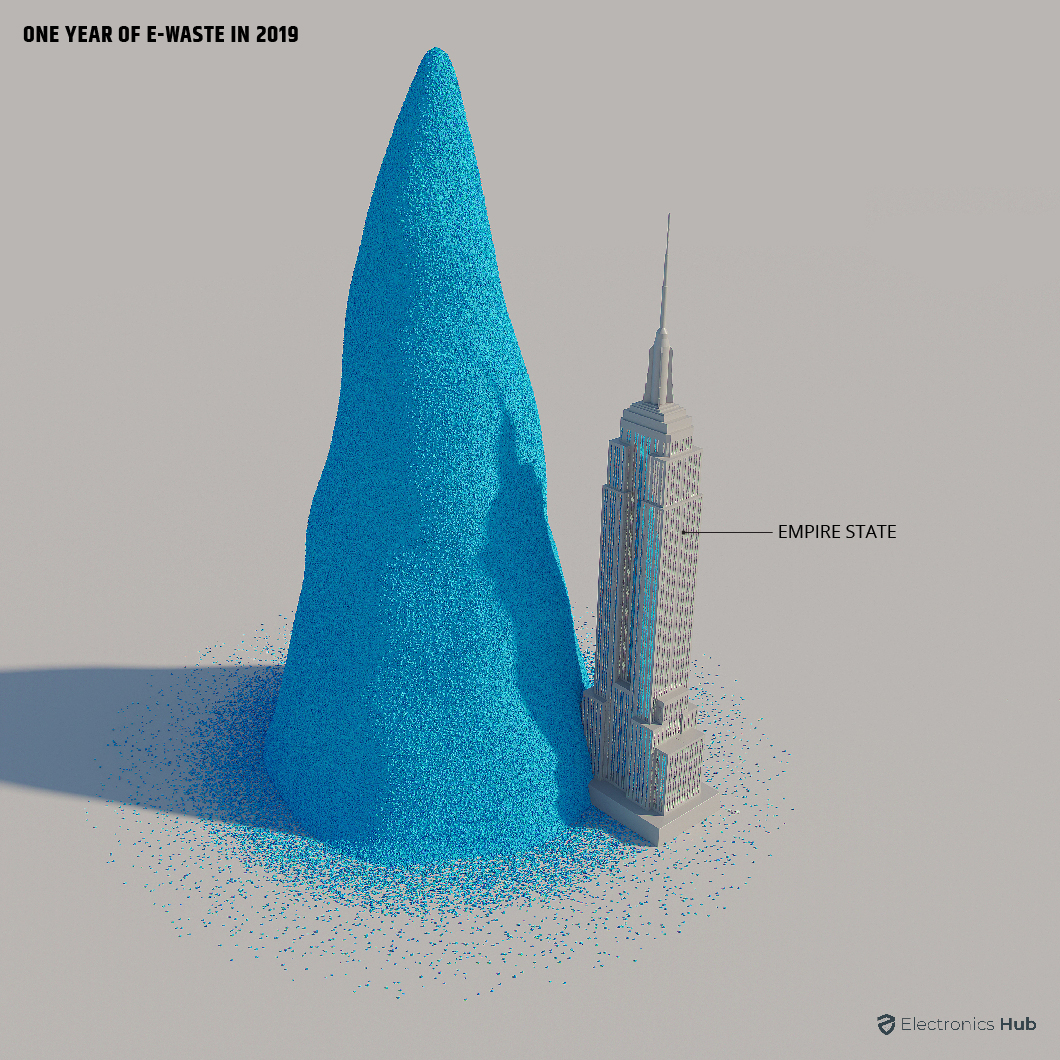

An e-waste Empire State Building every year

Humans dumped 53.6 million metric tons (Mt) of e-waste in 2019. This was a rise of 9.2 Mt in five years. The growth in e-waste is outstripping the growth in recycling activities.

Electronics are getting more and more lightweight. Yet the tonnage that gets wasted year after year continues to rise.

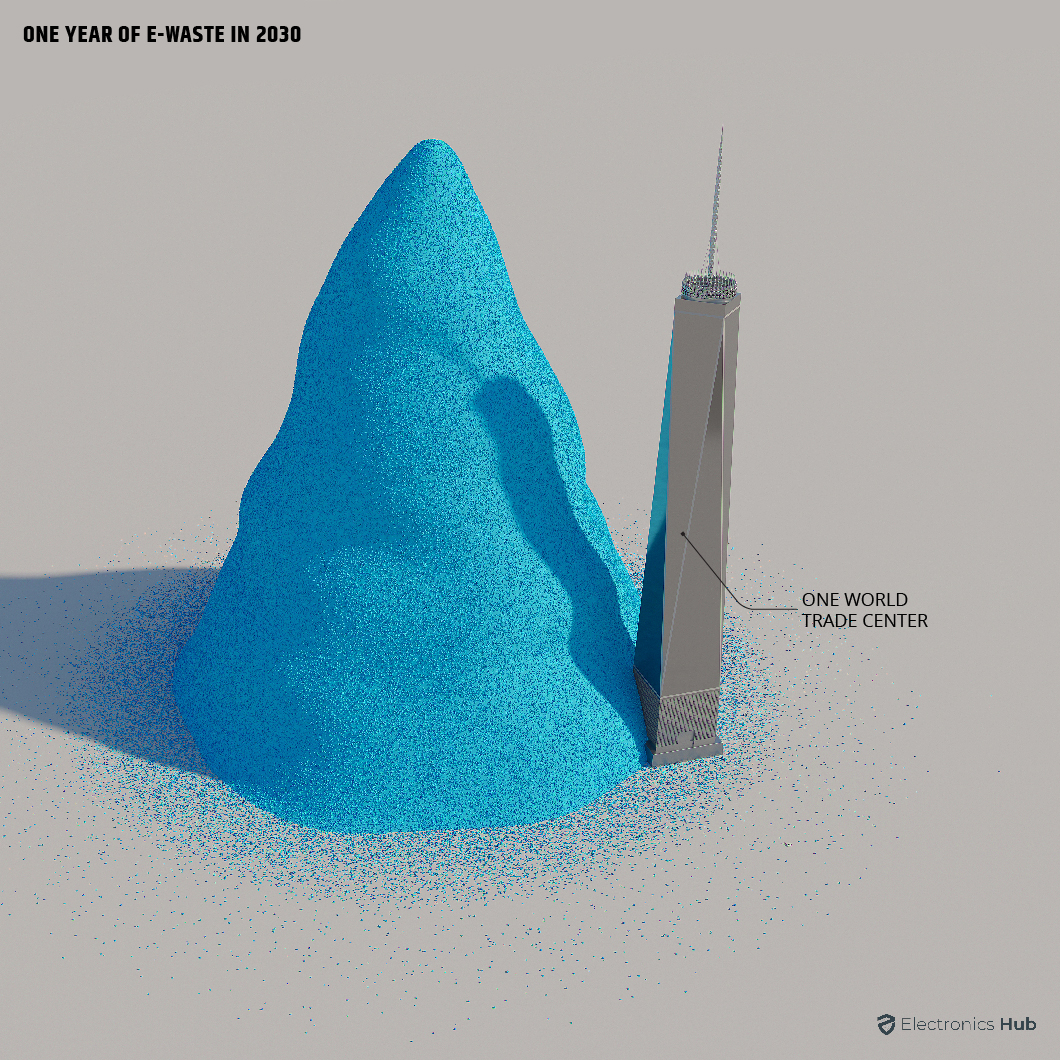

An e-waste One World Trade Center per year by 2030

By 2030, measured by our trusty iPhone 11 brick, the world’s annual e-waste is projected to engulf the tallest building in the Western Hemisphere: the One World Trade Center. The One World Trade Center reaches 1,776 feet from its foot to the top of its spire and has a footprint of 40,000 square feet:

You’re looking at 74.7 million metric tons of discarded iPhone 11s – the amount of e-waste we’re expected to generate annually by the year 2030.

Worldwide Electronic Waste Production, Mapped

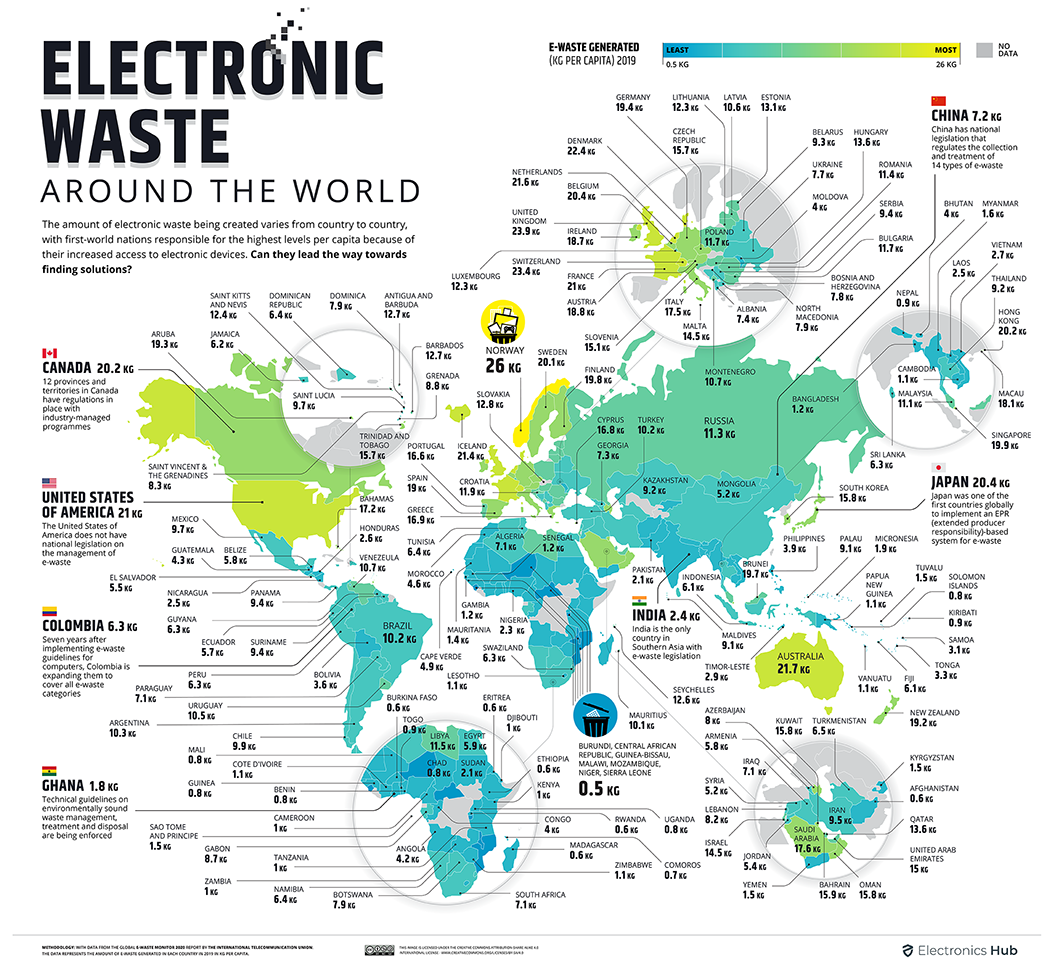

E-waste is not distributed equally. Manufacturers source components, including precious metals and minerals from low-income countries. Consumers use and dispose of them in western and high-income Asian countries. And manufacturers and authorities send them back to low and newly emerging economies, including China and India, to be ‘recycled.’ This map shows the amount of e-waste generated by every country compared to the national population:

One of the world’s wealthiest nations, Norway, is the country that produces the most e-waste per head. However, this figure may be high partly because e-waste disposal is highly regulated in Norway. Other countries may produce more waste than is documented.

European countries (including non-EU Norway, UK, and Switzerland) occupy the top ten spots for e-waste produced per capita, accompanied by Australia and the US. Eighteen of the 20 countries with the lowest e-waste are in Africa.

Right To Repair Laws Around The Globe

Recycling is not a cure-all. It can be an energy-intensive process with unforeseen costs for people and the planet. Dropping things off to be recycled makes us feel good about ourselves, but the fate of much of the waste sent abroad for processing is a mystery.

“A substantial proportion of e-waste exports go to countries outside Europe, including west African countries,” according to Interpol. “Treatment in these countries usually occurs in the informal sector, causing significant environmental pollution and health risks for local populations.”

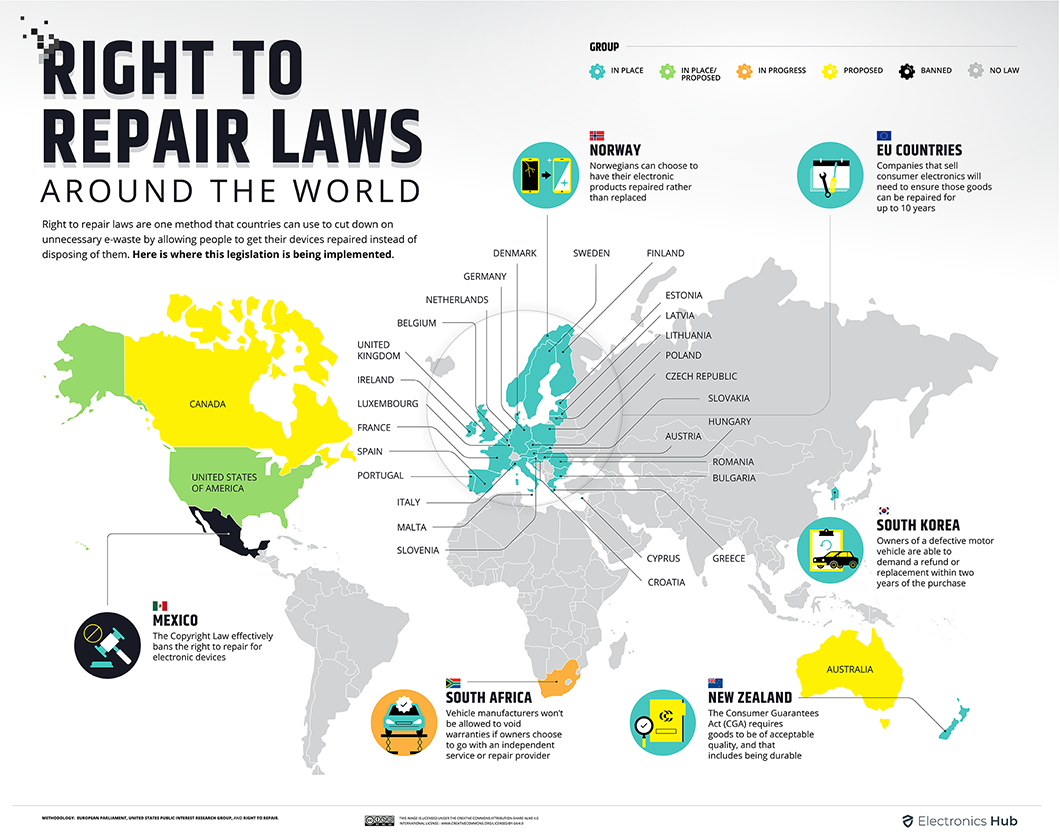

Over recent decades, the common mantra has been ‘reduce, reuse, recycle,’ and it’s important not to underestimate the power of reduction and reuse. But a fourth option is gaining traction as the right to repair movement grows.

Campaigners want manufacturers to create goods that can be easily repaired. Companies should detail how long a product can be expected to last and make spare parts available to aid repair long after warranties expire.

In South Africa, legislation now forbids vehicle manufacturers from voiding a warranty if the user goes to an independent repair service. In theory, this should make repair a more affordable option than replacement. In Mexico, a new copyright law effectively bans the right to repair electronic devices.

The European Union requires manufacturers to make spare parts available for up to ten years and to come with a repair manual. Goods must also be made in such a way that they can be easily dismantled. Sweden has built on this law by reducing value-added tax for repairs and spares.

The State of Right To Repair Laws in America

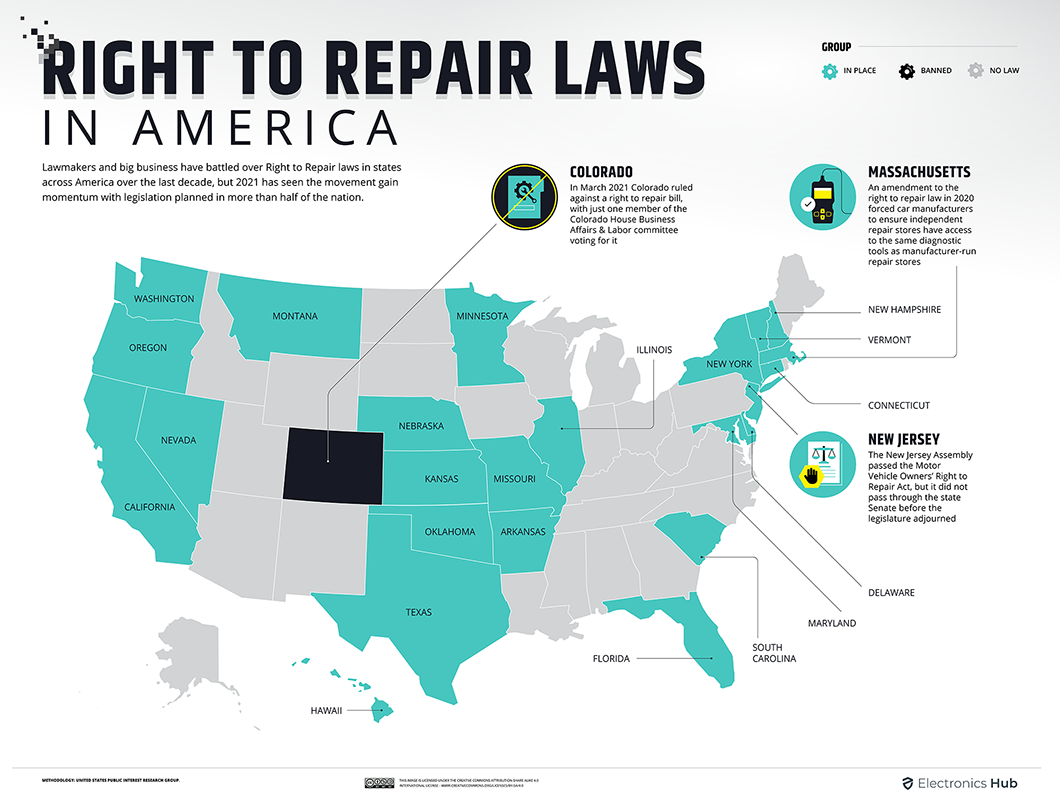

Meanwhile, the right to repair movement has reached a watershed moment in the United States. As of March 2021, 25 states have considered active Right to Repair legislation – although the devices covered by the law vary from state to state.

A report from U.S. PIRG found that the average household spends $1,480 per year on electronics and could save $330 by repairing instead of replacing (a national saving of $40bn). Despite this, the Colorado House Business Affairs & Labor committee recently shut down a proposed right-to-repair law for the state.

Take It Apart to Put It Back Together

As with the climate crisis, the ultimate power and responsibility for e-waste, recycling, and right to repair, belongs with governments and corporations – no matter how hard they try to place the blame on consumers.

But consumer responsibility is essential if the cultural shift to a ‘repair society’ is to occur. Right-to-repair laws are hard-won: they require campaigners to push them through, and once legislated, they require consumers to make use of them.

Next time your vintage laptop or struggling desk fan gives up, consider attending a repair café or similar. This can be an informal (and often free) place to meet experts who will help you mend your electronics, even if you have no idea what you’re doing.

Whether it helps you become a mender or just opens your eyes to the global subculture of tinkerers and fixers, it is a step towards a society where resources are used to their full capabilities instead of buried as landfill or disassembled at great cost to your health and the environment.

Comment * Name * Email * Website

Δ

![]()